A couple weeks ago we visited Mexico City to celebrate 40 years of life and living 20 years with my genetic muscle wasting disorder, GNE Myopathy . I documented most of my trip on my instagram while I was traveling and I plan to do a video and blog post of my Mexico travels and accessibility at a later date, but my entire reason for visiting Mexico City was Frida Kahlo's house so I wanted to share what I wrote about visiting Frida’s house. The people of Mexico City were wonderful, warm and always eager to help us. We had a beautiful experience.

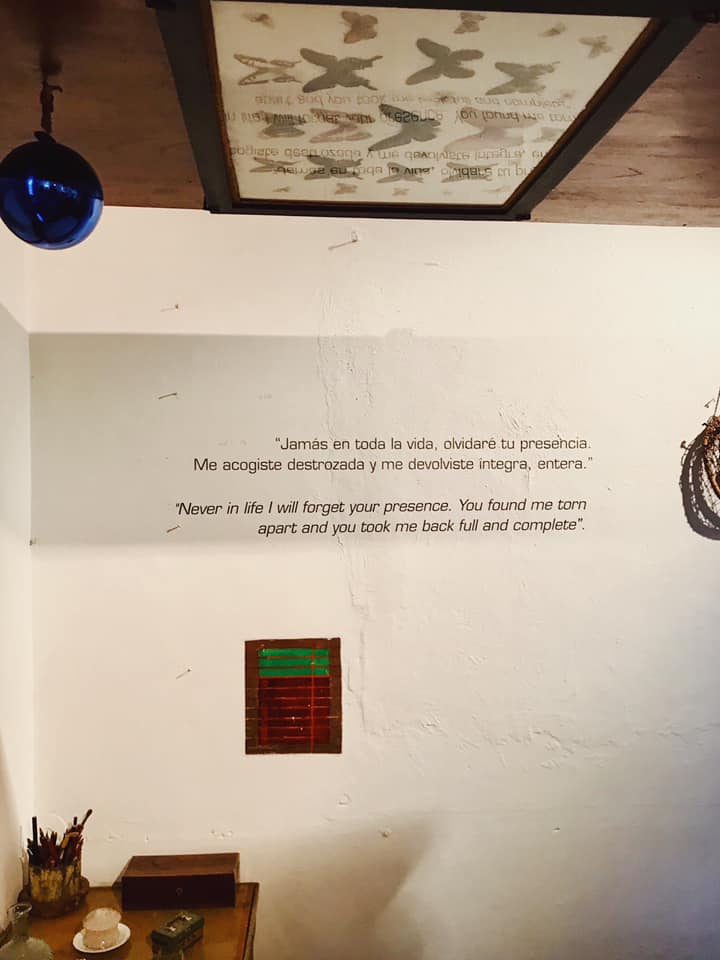

Here is some of what I wrote in her courtyard in three parts:

“Unknowingly my life has paralleled much of Frida’s life, views and character traits. For one, she and I have had some kind of health issues since childhood, and on a whim, as a self-taught illustrator, I turned to art as necessity to explain what is happening to me.

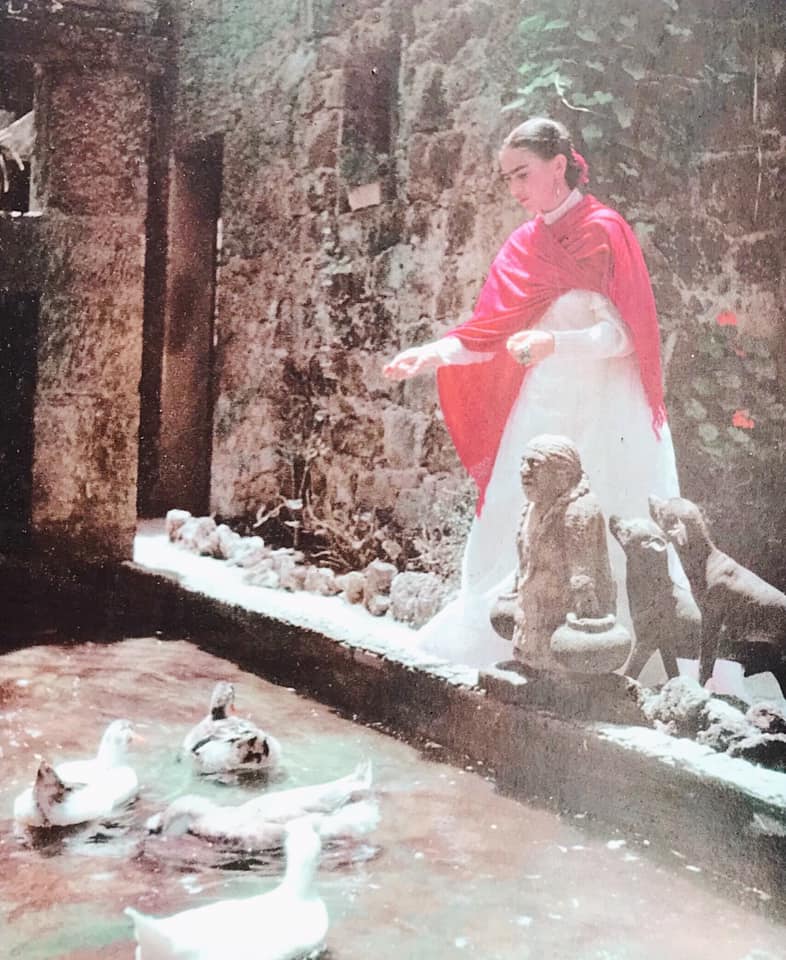

Frida was a child among the Mexican Revolution, the daughter of a bohemian German father and Mestiza mother, and considered one of Latin America's greatest and most recognized artists. She was born in La Casa Azul (the blue house) in Coyoacán, Mexico City where she was raised and lived most of her life. She ultimately died in her childhood home. In the 21st century Frida's name has been haunted by labels like ”surrealist”, and feminists and LGBT claim her as their own but Frida abhorred labels. To me Frida was Frida: someone who was ahead of her time in terms of living outside society’s boxes and, who frankly, didn’t give a damn what others thought.

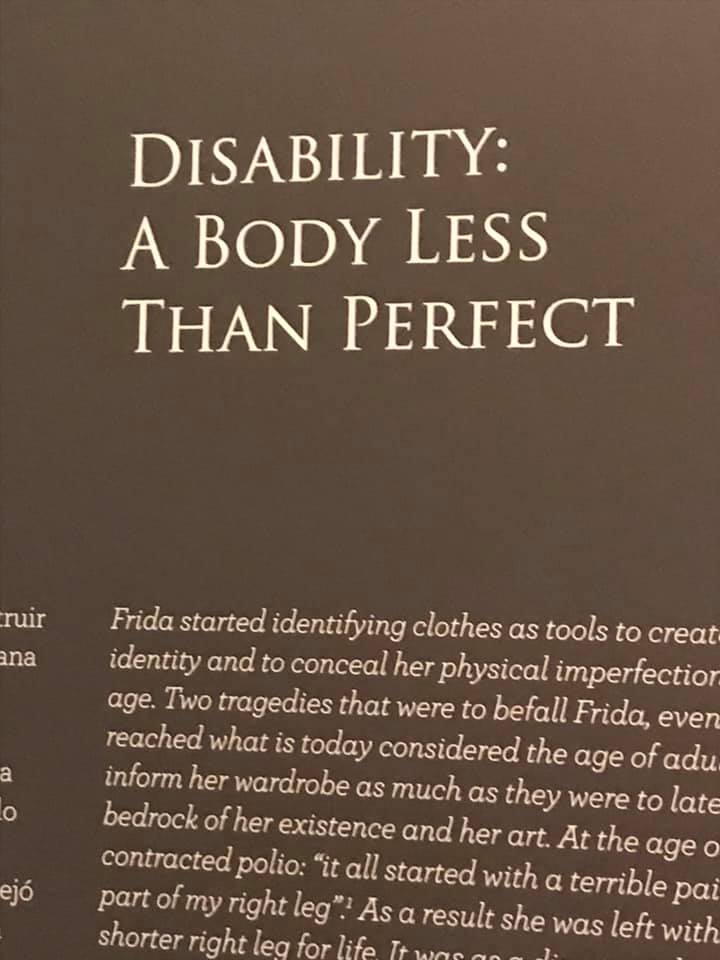

While Frida was regarded as a surrealist, she was adamant her art was not surrealism yet her daily reality. As a child she had contracted polio and learned early on what it’s like to be consumed by your body. At 18, she was to go to school to become a doctor when a gruesome trolley accident completely changed the course of her life. She was left with multiple broken bones and a lifetime of severe pain. An iron handrail penetrated her hip — piercing her uterus and exiting through her vagina, leaving her unable to have children.

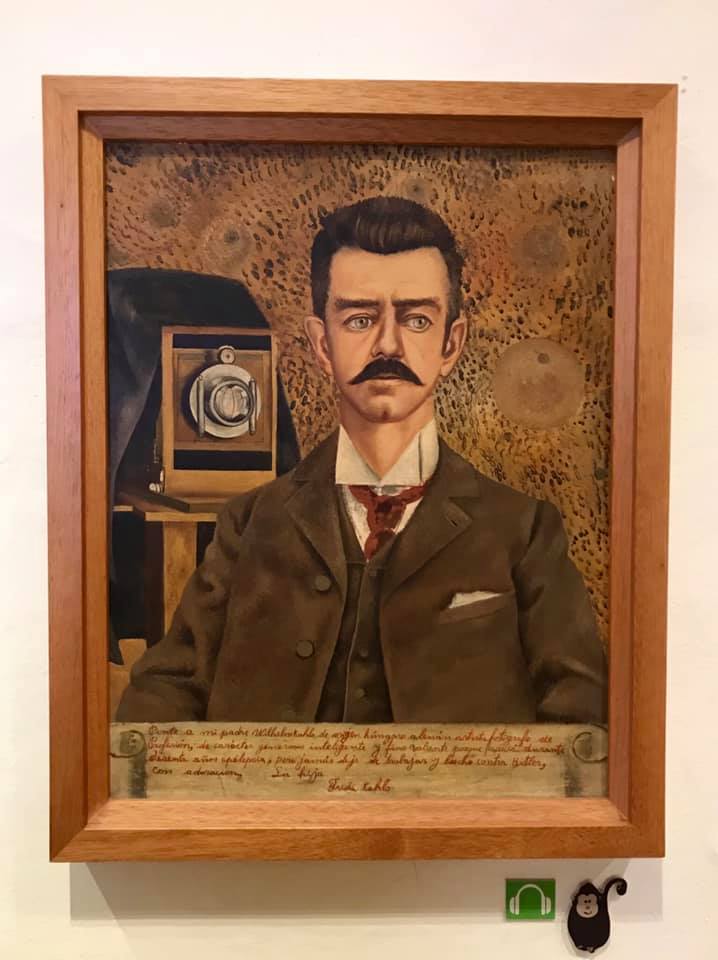

Though regarded as a feminist it was the men in her life who influenced her most: the first man being her father, a well-known photographer. After polio it was her father that encouraged her to do sports like boxing, soccer and even wrestling which was highly unusual for girls at the time. She assisted her father in his photography and began understanding framing, posing and capturing subject matters.

After her accident Frida was bedridden and it was her father who encouraged art, building her a special easel so she could paint from bed. Originally she thought medical illustrations could be a compromise; combining her love of science and art. Instead she found art could reflect her inner voice and turmoil. But her art didn’t really begin to reflect the vulnerable Frida we’ve come to know until later in her painting career. In fact, it was early 1930s while living in Detroit when Frida, who was accompanying her husband and famous painter in his time, Diego, on a mural project for the DIA, consciously decided to tell her story and reveal herself through painful intimacies slathered on canvas. Detroit is where she endured a severe miscarriage and couple years later the death of her mother. Due to her accident she endured 3 miscarriages. One was a forced abortion to save her life. Not being able to have children was a profound reality that haunted Frida and her work until the end of her life, something I can relate to.

My family grew up in small town white suburbia pretty far from Detroit so I was the only one who had any real experience in Detroit as I lived there for 5 years during college years. I didn’t live far from that Diego DIA mural and the Henry Ford Hospital where Frida miscarried.

From then on Frida began creating the works that most define Frida as an artist, including her complete embrace of her indigenous side and nearly shunning her European roots. Her identity in Mexican folk art and fashion permeated her life. Her intense interest in fashion was a form of disguising her “broken body”, as she said, and unremitting physiological and emotional pain.

Through the chronic illness world I've learned many who endure chronic pain or chronic illness will compensate with fashion and makeup to be something besides the endless pain.

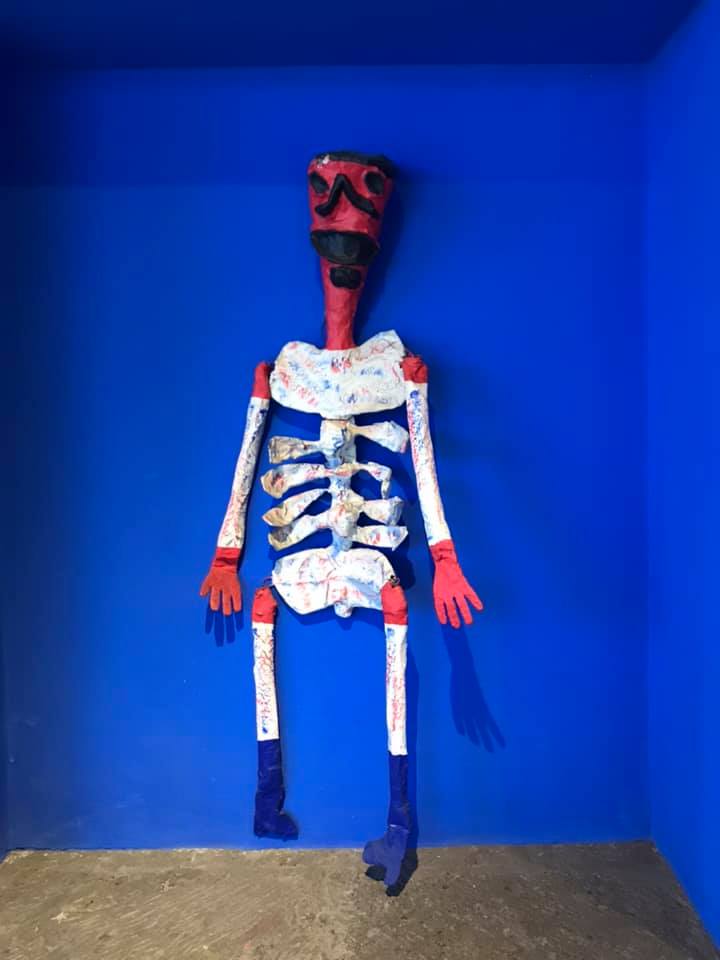

Frida’s art is unafraid of pain and death. She painted love, uncompromising pain, surgeries, socio-politics, cultural identity, fertility, classism, death and a deep yet complicated passion for her husband, the famous Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

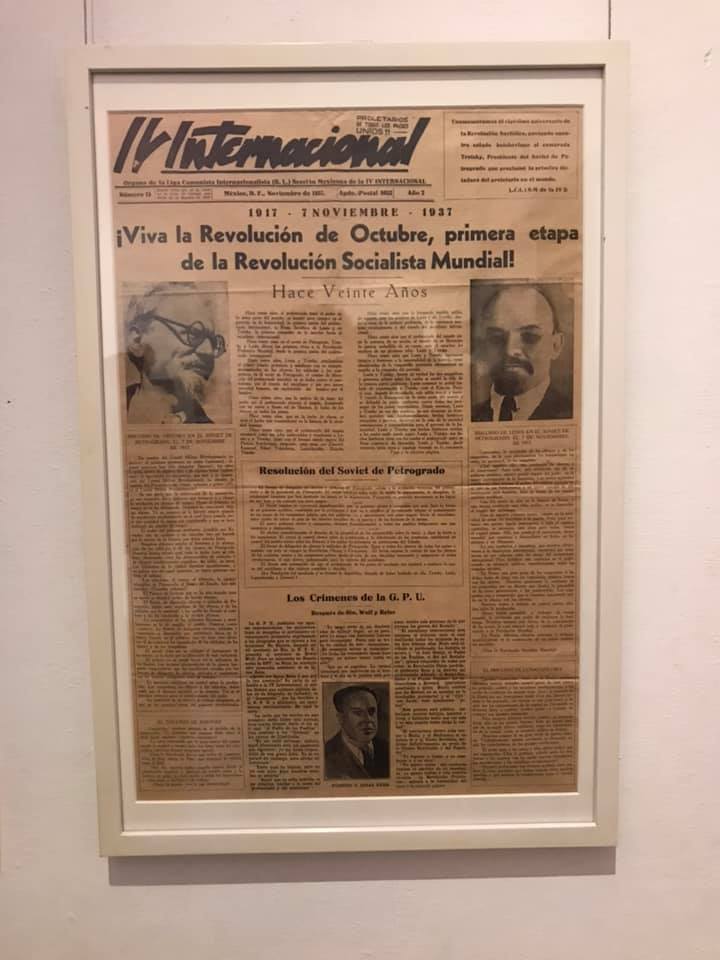

Frida was active and loud in the political, intellectual, cultural, literary and artistic movement. Her and Diego often hosted fellow artists, thinkers and socio-political revolutionaries. She rejected and loathed the bougie art world of Europeans. She had no use for elitism and possessed more heart and interest in the “carpenters and cobblers” than the supposed “civilized herd of windbags known as cultivated people” like the “pretentious and superficial” Parisians.

She preferred to pay attention to the everyday person; those in misery rather than the “fat cats” of society who partied the people's' money away while the poor suffered. She was against Europeans endless colonialism and US’ imperialism that favored the wealthy and kept the working class down. She was against (US) foreign domination imposing their economic interest onto Latin America (something BOTH US parties have been doing for decades, there and worldwide.). And in her last days she participated in demonstrations against US’ CIA intervention of Guatemala.

I call her a painter of the people.

She was an intellectual without calling herself one. She was a woman who endured 38 failed surgeries. Despite her pain-filled paintings she was feisty, outspoken, tenacious, revolutionary, self-affirmed, charismatic, erotic and tormented in love and life. She was a smoker, heavy drinker, cussed like a sailor and turned to drugs to dull her pain. She had sensational love affairs and MANY at that.

Frida's love for Diego was tortured most of her life by his inability to be monogamous and his lustful wandering; a man who clearly was “unpossessable” despite his undying affection for Frida. But Frida was no monogamous angel, either, having lovers in both men and women, including entertainer Josephine Baker.

But by 1950 her health issues were all-consuming. She died at 47. Official cause of death was pulmonary embolism but those close to her, including her nurse, believe it was suicide since she was suicidal most of her life.

Through the years I’ve gotten to know more about Frida’s life and have previously written a blog post about her life. Obviously with my own experience as a disabled artist I’ve come to understand her even more.

Courtyard view into Frida’s bedroom where she spent much time in bed due to chronic pain and health issues from a horrific accident.

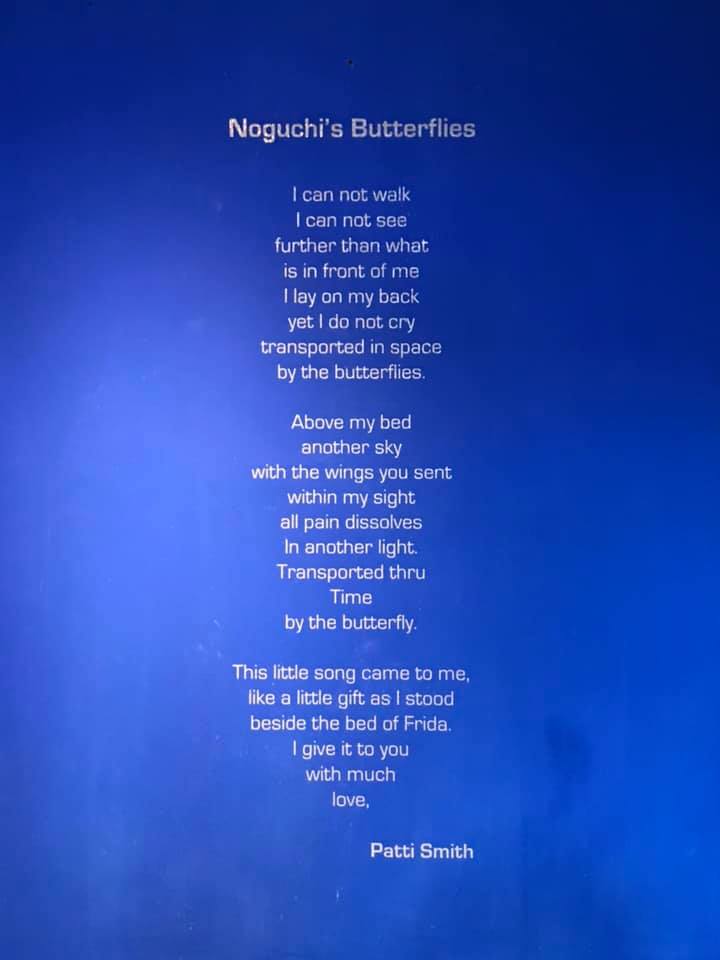

“Pain is always new to the sufferer,” wrote the 19th-century writer Alphonse Daudet living with syphilis “but loses its originality for those around him. In the Land of Pain. Everyone will get used to it except me.”

Spectators get used to Frida’s pain but she never did. And like a glamorous cliche we placed a glowing “halo of suffering” over her name.

Stelarc said, “Awareness is what happens when the body malfunctions.” Pain is ineffable. “It splinters the self and impedes all efforts to maintain a coherent self”, vanquishing one’s desire to be understood.

Splitting oneself from the pain is a common psychological response to pain & trauma; an unconscious survival technique. Frida split herself through art.

As I sat there in Frida’s courtyard I wondered the persistent thoughts that roamed her mind when she was most alone. Her dreams, her tales & waking dreams while she documented what she could. No doubt she had thousands more thoughts undocumented. If I had the energy I would be drawing all the images that run through my mind, but instead we are often coping with the general arrival of the day, anything extra is a luxury.

I don’t think of Frida as a famous painter, yet a multi-faceted woman who was often locked inside her bedroom, forced to receive the world through her mind & mirror, extending her voice to the world through art.

Frida was not an icon when she painted. She was a human, a daughter, a wife and a lover who often felt alone in the depths of pain by a body that imprisoned her yet didn’t own her.

In spite of it all, according to her friend, she ‘lived dying’ yet at the same time was completely in love with life. Through my own experience I have a decent idea of what this means. While there’s a trail of crumbs that connect us all, the experiences of disabled, undiagnosed and chronically ill are individually unique. It’s a story that involves our past and a reckoning of life that exists beyond the fairytale Disney stories that warp our minds from a young age.

I hate how we romanticize artists into tragic tortured beings. We are merely a window. To only view her as a tragic figure washes her life away. A life is multi-dimensional. Perhaps artists see life in a different stroke, but the only difference between us is artists can vulnerably communicate what so many feel.

Frida wanted to be a doctor. Everything she loved to do or wanted seemed to be at arm's length, like her dream of having a baby. I live this every day. So many do. But life reconfigured her desires and all she could do was either bare it and adapt or perish.

I sat in her courtyard wondering how she felt when all her famous artist friends weren’t around or when she wasn’t doing what she loved most; hosting dinner parties and connecting. I felt how lonely it is to know how alone we really are in struggles of health. When we are happy, we aren’t lying. But we are multibranched and able to feel many things in one day. But when you’re alone you are a version that people don’t normally see.

Dealing with progressive weakness the last 20 years due to my genetic myopathy, and now an undiagnosed new chronic chamber, has been difficult — sometimes unbearable. Weakness resonates, pain permeates. But it happens slow, so you adjust, like baby steps inching towards walking only to be knocked down again.

Since I’m so public I’ve met many people around the world sharing their stories. This world is so vast, yet so intimate. We pass each other on social media and secretly peek in over a trove of stories. While there are many negative and shallow points of social media much good can come from it, if used correctly, like connection through shared experiences. Connections through shared experience, despite never meeting, are sometimes so much deeper than relationships we’ve had our entire life. And this is because at the end of the day we all deeply want to be heard and understood. We want to know that somebody gets it and our private moments of great difficulty aren’t lost in vain.

I wonder what Frida, whose only tether to the world was painting how it feels, thought. She didn’t have the world of social media to connect, to be heard or understood. What she saw was entrenched inner caves of humanity: the kind of pain most never see and the kind of loneliness that vibrates through souls too quiet to be heard.

I’ve always been very sentient since I was a child. I went through periods of sadness, not necessarily for myself but in understanding how the world really works. For those who are exploited, injustice, loneliness and shame that, by design, keeps us hidden.

Now that I have a tangible experience representing all the things I just mentioned, the feeling permeates much deeper. It gels and interlocks, and somehow the imagination required to understand those who struggle and are different is much less. Empathy is imagination. If we can imagine someone else’s life we have the ability to visit differences unsullied. When we empathize our scope of life is changed evermore.

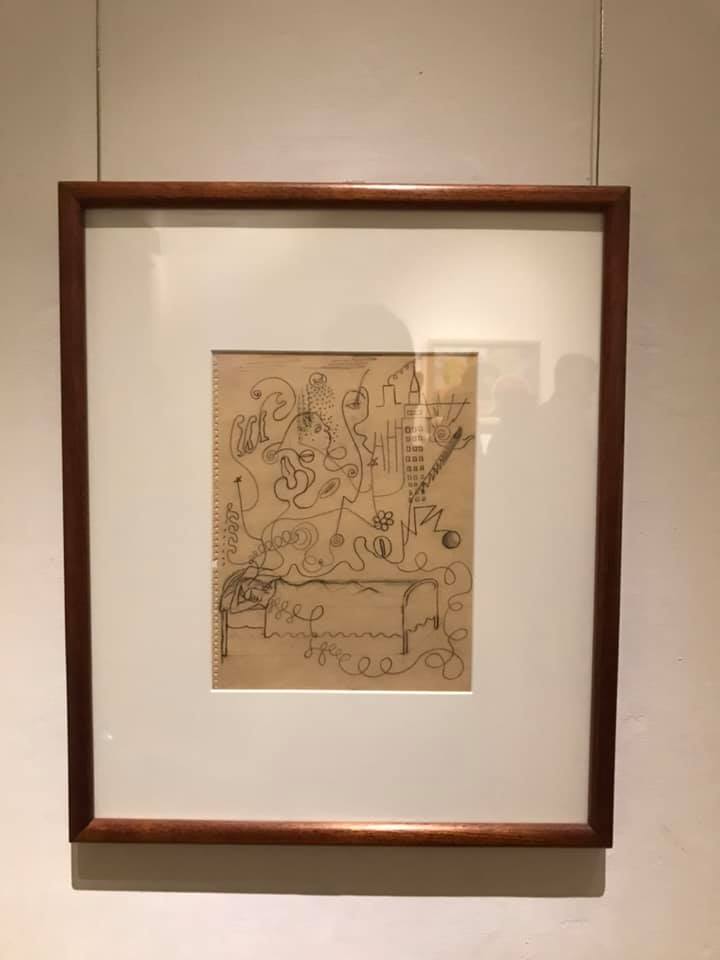

Here is Frida’s art studio, bed/bedroom where she died and some personal belongings.

“And Frida is the sole example in art history of someone who has torn open her breast and her heart in order to tell the biological truth of what she feels inside them.” -Diego Rivera

For all of Diego’s flaws he didn’t believe in society’s rule of men dominating women, which was unusual back then. He truly believed Frida was the real artist in comparison to himself. When Frida died Diego turned her childhood home into a museum to honor her. Diego died three years later. After Frida died grief-stricken Diego sealed away many of Frida’s clothes, photographs, earlier art and letters in a locked makeshift closet adjacent to Frida’s bedroom with instructions to keep them hidden for 15 years after his death. Her belongings remained hidden for 50 years, many of them adorning her childhood home, now a museum.

I always felt connected to Frida but when I was younger I don’t remember placing a lot of emphasis on why she painted. I knew of it but didn’t understand it. I only knew she was significant because she was a female artist in a time when women were not receiving recognition in a male dominated industry. This is still true today.

Art can explain what words cannot. Art and creativity can transcend struggle, even if for a moment, and is a visual relic encompassing a vision, a snapshot or a window into a bigger picture or reason.

Frida didn’t get to leave her house much during the most difficult stretches of her health, especially towards the end. But they often hosted. She loved her belongings and trinkets brought by friends around the world because it was her connection beyond her four poster bed. She used fashion to give herself a voice in a voiceless body and disguise what she considered was broken.

My art gallery

Follow my wheelchair travels, art and mini-memoirs at Instagram.com/kamredlawsk and Facebook.